Rediscovering appreciation for the food we partake through shojin ryori

Shojin Ryori is traditional Japanese cuisine based on the teachings of Buddhism, and is served at some Buddhism temples in Japan. You probably know that it is served without fish or meat, but that’s not all. Shojin Ryori, which has a history of 700 years, has a lot of tips to make your life more sustainable and improve well-being.

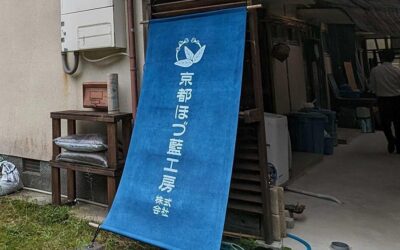

Akasaka Teran is a cuisine workshop in which you can learn such Shojin Ryori cuisine. It is in Jokoku-ji temple, located quietly in the town of high buildings in Akasaka, Tokyo. The teacher, Masami Asao, is originally a registered dietitian and started to make Shojin Ryori when she got married to the Buddhist priest of Jokoku-ji temple. She studied Shojin Ryori by attending the Shojin Ryori cooking lesson in Torin-in temple in Kyoto monthly. She wanted to give someone the knowledge she learned, so she decided to start Akasaka Teran 13 years ago.

Since then, she continued the Shojin Ryori cooking lessons using seasonal ingredients. The lessons are also popular among people from abroad. In fact, students from Poland, Ireland, Spain and Israel came to learn Shojin Ryori. She also visited the U.S. almost twice a year to lead Shojin Ryori cooking lessons in New York and Los Angels. She offers monthly online lessons on Zoom since she stopped visiting the U.S. because of the pandemic.

“Some people come to the lesson for the purpose of dieting and losing weight at first, but they become interested in the deliciousness of Shojin Ryori and understand it takes a lot of time and effort to make it,” she said.

Shojin Ryori cherishes every life

Shojin Ryori is a cuisine brought to Japan and developed together with the teachings of Buddhism. Its original rules require eating simply and forbid killing any living creature. Initially, it was the cuisine of Buddhist monks, but it was spread to the people because they had opportunities to eat Shojin Ryori at their relatives’ memorial services.

Shojin Ryori has many doctrines, not only avoiding animal-based dishes, but also using up all the ingredients for zero waste. It is usually served with one soup and three vegetable dishes, including valuing the sense of the season, serving with the heart of hospitality, and eating with gratitude and a calm mind.

“In Shojin Ryori, you think ‘everything has life.’ So, you must deal carefully with everything, including vegetables, seaweed, and water. Shojin Ryori is a cuisine where you cherish the lives of each ingredient and yourself.”

In the past, many Japanese treated the anniversaries of their relatives’ death and the annual Buddhism-related days as “Shojin days,” avoiding any animal-related materials. I had the same experience when I was a child. However, such traditions are disappearing among nuclear families and in the age of plenty. Shojin Ryori is not familiar to many Japanese people anymore.

On the other hand, more and more people are becoming vegan or vegetarian worldwide from the perspectives of climate change countermeasures and animal welfare. Part-time vegans, who take in vegan food once a week, also seem to be similar to the idea of a “Shojin day.” Shojin Ryori is probably the dietary method the world needs now.

Great hints for sustainable life

“Be satisfied with what you have,” Asao said when I asked for an essence of Shojin Ryori you can put into your sustainable life. “Without that idea, you will pursue everything forever. We have to live humbly because everything, including the sunlight and water, is limited. My teacher, the priest of Torin-in temple, always says, ‘Awaken the heart to save lives.’ I take the meaning of these words to utilize ingredients as much as possible while recognizing they are limited. You must not increase the amount of garbage by handling carelessly or buying too much and throwing it away. Cooking means keeping the life of food and using it for yourself. Therefore, you have to make the best use of it. And I think we have to be grateful that we are alive thanks to everything.”

She recognizes the environmental problem through the ingredients she always uses. “Kombu, an indispensable seaweed for soup stock, is becoming difficult to obtain in the past production areas. According to a clerk in the food shop, it doesn’t sprout and doesn’t grow large even if it sprouts due to the high seawater temperature. I feel it’s a crisis when I see such conditions that what used to be commonplace is no longer so.”

She said that the important measure to the environmental problem was also to consider ways to “be satisfied with what you have” in your daily life. “We tend to focus on the large measures such as decarbonization or the end to nuclear power, but I think we must focus more on ourselves and be satisfied with what we have in the daily life first. We need to recognize electricity, gas, and water are limited, and avoid wasting them.”

What Asao wants the world to know

What she wants to do from now on is to further promote Shojin Ryori around the world. “The cooking class is ‘sowing seeds.’ I hope that the seeds sown in the students will someday sprout and leave Shojin Ryori for posterity. I’m expanding the range and brushing up by incorporating Shojin Ryori dishes of temples of other denominations so that everyone wants to make them. In my new, upcoming cooking lesson, ‘Shin Shojin Ryori,’ you can learn new Shojin Ryori dishes such as bechamel sauce that does not use dairy or animal ingredients. ‘Shin’ of the name ‘Shin Shojin Ryori’ means new, but I use the Kanji meaning ‘heart’ that is also pronounced ‘shin.’ The goal of the new course is not only to make new dishes but to enrich the heart. I want to aim for the words “thank you” to be born naturally from the students.”

She wants people worldwide to know “the importance of caring for others” through teaching Shojin Ryori. “In the cooking lesson, students are separated into groups and make dishes. Sometimes in the overseas lessons, a group that has finished cooking will start eating quickly, even though the other groups are still making. I tell them to wait for all groups, and say ‘Itadakimasu’, spoken at the beginning of meals, all together. It’s the same as finishing a meal, you must wait for everyone to finish eating and then say ‘Gochisosama deshita,’ which is traditionally spoken at the end of meals. It’s a common custom for Japanese people but not for the other people. Behind this custom lies the meaning of ‘the importance of caring for others.’ To think about the person who is late and wait, even if your dishes get cold. If everyone has compassion for the others, it will be a world where everyone can live more comfortably.”

Originally published on Zenbird.Media.

Watch the excerpt video of the event Zenbird did with Akasaka Teran.